United States Navy Camouflage Doctrine

Dec. 17, 1941 to March 1943

Immediately following the attack on Pearl Harbor, priorities for the USN shifted dramatically. Camouflage, although an official requirement, instantly took a back seat to logistical, strategy, and naval operations in both the Pacific and Atlantic. Although operational priorities dominated after Pearl Harbor, BuShips continued refining camouflage doctrine through its newly formed Camouflage Section in early 1942. 1941 was a tumultuous year for naval camouflage development because the USN was still trying to figure what type of camouflage system was optimal. If anything, 1941 proved that none of the systems were perfect, and the losses of the British battleships Prince of Wales and Repulse three days after the Pearl Harbor attack only highlighted the increasing importance of visual concealment and aircraft defense, even if camouflage itself played little direct role in their fate.

What the USN was looking for simply didn’t exist – a system that combined concealment from detection and confusion of enemy aim once sighted. Concealment is exactly that – hiding a ship so that it is not seen. Since warships are not exactly small and good at hiding, confusion then plays an even more important role, for once the ship is spotted, disguising the shape of the vessel, it’s course and speed, are all important factors when engaging that ship with naval gunnery or submarine torpedoes.

When the U.S. entered World War II, the Navy had no unified camouflage doctrine. Prewar studies by the Bureau of Construction and Repair (BuC&R) and Bureau of Ships (BuShips) had produced various Measure schemes (notably Measures 1–13) but there was no central command guidance.

On December 16, 1941, BuShips issued Confidential Circular Letter 10-41, revising wartime camouflage doctrine to reflect new urgency and lessons from the British Admiralty. This letter was primarily instructions for all commands to start utilizing the SHIPS-2 documents that had been officially released in September of 1941.

Early War Doctrine (December 1941 – mid-1942)

- Measures 1 through 13 (Prewar / Early War Transition) By December 1941, the following schemes were officially recognized:

- Measure 1: Dark Gray overall (Navy Gray #5-D) — prewar standard for battle fleet ships.

- Measure 2: Graded system (Dark Gray upper hull to Light Gray #5-L topsides).

- Measure 3: Light Gray overall (for visibility reduction).

- Measure 11–13: Experimental blues and grays, limited use prewar.

- Measures 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 were discontinued by the end of 1941. Measures 9 and 10 were submarine measures, overall black (Ms9) and 5-O Ocean Gray (Ms10).

USS Drayton in a perfect Measure 1b using experimental Sapphire Blue. Sapphire Blue was a perfect color, but chemically faded too quickly and was not implemented.

Measures 1 and 2 respectively were deemed to possess the best overall qualities for concealment and deception but were already discontinued in SHIPS-2 by December ‘41. Since there was no

"perfect" camouflage measure, the USN adapted variations of Measures 1 and 2 in conjunction with their new colors, 5-N Navy Blue, 5-O Ocean Gray, and 5-H Haze Gray. 5-D had already been discontinued, and 5-S Sea Blue was officially discontinued on Dec. 16th of 1941.

Measure 1 was replaced with Measure 11 - overall 5-S Sea Blue, and when new construction warranted, 5-N Navy Blue until all stocks of 5-S were depleted. Overall 5-N Navy Blue was still referred to as Measure 11 until June of 1942, when it was officially re-named Measure 21.

USS Saratoga at Pearl Harbor in early 1942 in Measure 11, overall 5-S Sea Blue.

Measure 2 was replaced by Measure 12 – a graded scheme using 5-S Sea Blue,

5-O Ocean Gray, and 5-H Haze Gray. When 5-S was discontinued and replaced by 5-N Navy Blue, this measure was listed as Measure 12 Revised. It was still a solid-demarcation

graded pattern.

USS Charles F. Hughes in Measure 12, 1942.

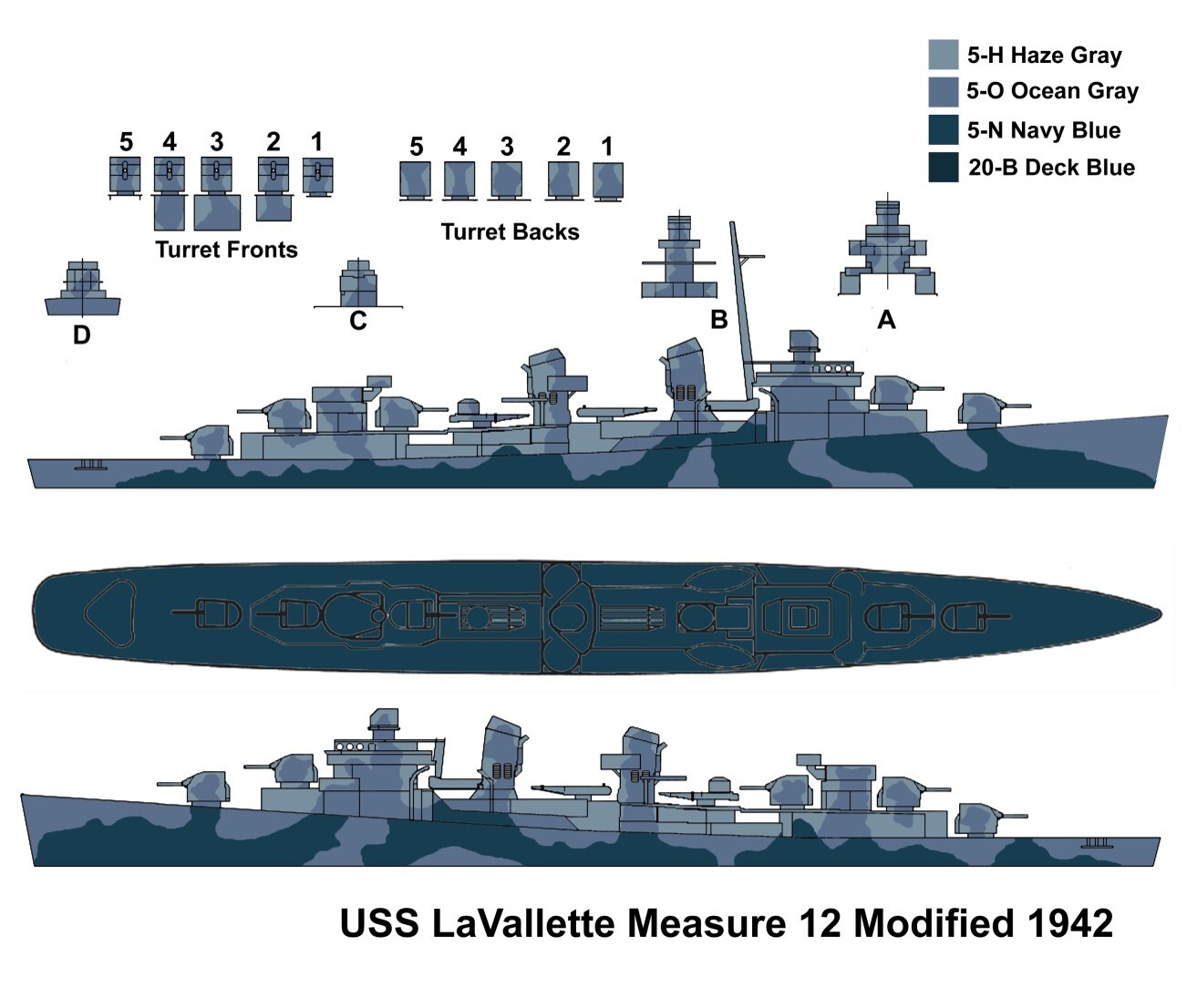

Measure 12 Modified versus Measure 12 Revised

The nomenclature has been used interchangeably over the years, primarily because Measure 12 Revised only related to 5-N Navy Blue in lieu of 5-S Sea Blue.

Measure 12 (Modified): In early 1942; combined graded tones with patterned areas on hull and superstructure — precursor to later dazzle systems. This caveat to Measure 12 appeared in the September ‘41 SHIPS-2, but does not appear to have gained any traction until March 1942, when memo C-S19-7 (341) indicates that the original caveat in Ships-2 works very similar to the Royal Navy’s Admiralty Disruptive Patterns.

USS Juneau in perhaps the wildest of Measure 12 Modified Schemes.

Measure 12 Modified consisted of the same three colors, but at the captains’ or yards’ discretion, allowed for these colors to overlap, creating a “splotch” pattern of camouflage designed to break up the outline of the ship at medium ranges. Standard practice was to have 5-O Ocean Gray over the 5-N Navy Blue on the hull, and 5-H Haze Gray over 5-O Ocean Gray on the superstructure. While there were instructions as to the application (not more than 33% of the hull or superstructure covered by the overlap colors) these rules were pretty much ignored. Ships painted in Measure 12 Mod were all unique – there are no design sheets. The only way a modeler can replicate a Ms12Mod pattern is to view photos of the original ship.

3. Institutionalization and Standardization (mid-1942 - March 1943)

Measure 21: By mid-1942, many ships repainted overall in 5-N Navy Blue , a deep blue-gray designed to blend with the Pacific. This was a simplified version of Measure 1 that removed the 5-L Light Gray from the masts of the ship. Remained in use until the end of the war.

Measure 22: Two-tone system — a simplified version of the original Measure 12, eliminating the 5-O Ocean Gray color from the measure and using 5-N Navy Blue on the hull to the main deck edge, and 5-H Haze Gray above. Came into widespread use by 1943 and remained in use until the end of the war.

Next Chapter - Development of Pattern Systems

Through late 1942, experiments with disruptive patterns were underway.

These were based on British Western Approaches designs but adapted for U.S. ship silhouettes.

By early 1943, the Navy had completed testing that led to the first formal “dazzle” (Disruptive) Measures 31–33, though these weren’t issued until April–June 1943.

4. Doctrinal Philosophy by March 1943

By the end of this period: The U.S. Navy emphasized concealment over deception (tone and contrast rather than geometric confusion).

Measure 21 and 22 were the operational standards, balancing visibility control with practicality. Research into disruptive and counter-shading continued but was not yet officially adopted.

The goal: reduce detection range and make range estimation difficult for enemy lookouts, particularly under variable Pacific lighting.

This information was written by Jeff Herne, and is from his lifelong research.